Προσευχές πλάι στη λίμνη 20

Σκέψου τον εαυτό σου σα να ήσουν νεκρός, λέω στον εαυτό μου και δεν θα νοιώσεις τον ερχομό του θανάτου. Λείαινε τα αγκάθια του θανάτου όσο ζεις και όταν έρθει δεν θα έχει τα μέσα για να σε τσιμπήσει.

Σκέψου τον εαυτό σου κάθε πρωί σαν νεογέννητο θαύμα και δεν θα αισθανθείς τα γηρατειά.

Μην περιμένεις τον θάνατο να έρθει, γιατί ο θάνατος έχει ήδη έρθει και δεν σε έχει εγκαταλείψει. Τα δόντια του βρίσκονται διαρκώς στη σάρκα σου. Ότι ζούσε πριν τη γέννησή σου και ότι επιβιώσει μετά το θάνατό σου - αυτό ακόμα και τώρα ζει μέσα σου.

Μια νύχτα ένας άγγελος ξετύλιξε την κορδέλλα του χρόνου, το τέλος της οποίας δεν μπορούσα να καταννοήσω και μου έδειξε δύο τελείες επάνω στην κορδέλλα. "Η απόσταση ανάμεσα σε αυτές τις δύο τελείες" είπε, "είναι η διάρκεια του βίου σου".

"Αυτό σημαίνει πως ο βίος μου έχει ήδη τελειώσει," φώναξα "και πρέπει να προετοιμαστώ για το ταξίδι. Πρέπει να είμαι σαν την εργατική οικοδέσποινα, που περνά την παρούσα ημέρα καθαρίζοντας το σπίτι και κάνοντας προετοιμασίες για την αυριανή εορτή της Σλάβας."¹

Αλήθεια, η παρούσα ημέρα όλων των υιών των ανθρώπων είναι γεμάτη κατά το μεγαλύτερο μέρος με ανησυχία για την επόμενη μέρα. Κι όμως λίγοι από εκείνους, που πιστεύουν την υπόσχεσή Σου, ανησυχούν για το τι θα συμβεί την επόμενη μέρα από τον θάνατο. Ας είναι ο θάνατός μου, Κύριε, ένας αναστεναγμός όχι για αυτόν τον κόσμο, αλλά για το ευλογημένο και αιώνιο Αύριο.

Ανάμεσα στα σβυσμένα κεριά των φίλων μου, και το δικό μου κερί, επίσης, σβύνει. "Μην είσαι ανόητος" επιπλήττω τον εαυτό μου, "και μη λυπάσαι που σβύνει το κερί σου. Στ' αλήθεια τόσο λίγο αγαπούσες τους φίλους σου, που φοβάσαι να πας ξοπίσω τους, πίσω από τόσους πολλούς που έχουν βολτάρει μακριά; Μη λυπάσαι που το κερί σου χαμηλώνει, αλλά ότι αφήνει πίσω δυσδιάκριτο και χλωμό φως."

Η ψυχή μου έχει συνηθίσει να αφήνει το σώμα μου κάθε μέρα και κάθε νύχτα και να απλώνεται στα όρια του σύμπαντος. Όταν απλώνεται με αυτόν τον τρόπο, η ψυχή μου αισθάνεται σα να κολυμπούν πάνω της ήλιοι και φεγγάρια όπως οι κύκνοι κολυμπούν πάνω στη λίμνη μου. Λάμπει μέσα από ήλιους και συντηρεί ζωή σε γήινους πλανήτες. Υποστηρίζει βουνά και θάλασσες. Ελέγχει τις βροντές και τους ανέμους. Γεμίζει πλήρως το Χθές, το Σήμερα και το Αύριο.² Και επιστρέφει στην πυκνή και σαραβαλιασμένη οικία της σε έναν από αυτούς τους γήινους πλανήτες. Επιστρέφει στο σώμα που ακόμα, για άλλο ένα ή δύο λεπτά, καλεί δικό της και που τρεμοπαίζει σα σκιά ανάμεσα σε σωρούς από τάφους, ανάμεσα σε φωλιές από κτήνη, ανάμεσα σε ουρλιαχτά από ψεύτικες ελπίδες.

Δεν παραπονιέμαι για τον θάνατο, Ζώντα Θεέ, δε μου φαίνεται να είναι κάτι λυπητερό. Είναι ένας τρόμος που ο άνθρωπος έχει δημιουργήσει για τον εαυτό του. Πιο δυνατά από οτιδήποτε στη γη, ο θάνατος με σπρώχνει να Σε συναντήσω.

Είχα μια φουντουκιά μπροστά στο σπίτι μου και ο θάνατος την πήρε από μένα. Ήμουν θυμωμένος με τον θάνατο και τον καταράστηκα λέγοντας: "Γιατί δεν πήρες εμένα, ένα αχόρταγο κτήνος και πήρες κάτι αναμάρτητο;"

Αλλά τώρα σκέφτομαι τον εαυτό μου σα να ήμουν νεκρός και κοντά στη φουντουκιά μου.

Αθάνατε Θεέ, κλίνε το βλέμμα Σου σε ένα κερί που αργοσβύνει και άγνισε τη φλόγα του. Γιατί μόνο μια αγνή φλόγα ορθώνεται προς Το Πρόσωπό Σου και εισέρχεται στο βλέμμα Σου, με το οποίο προσέχεις τον σύμπαντα κόσμο.

1. Σλάβα - (Σερβική λέξη που σημαίνει "δόξα") στη Σέρβικη Ορθόδοξη εκκλησιαστική παράδοση, οι τελετές που γίνονται με ειδικό άρτο (κόλατς) και οίνο για να δοξάσουν τον προστάτη Άγιο της εορτής συνήθως συνοδευόμενες από πολυτελές γεύμα και πολλούς καλεσμένους στο σπίτι κάποιου.

2. "Ιησούς Χριστός ο Αυτός χθές, σήμερον και εις τους αιώνας" (Εβρ. 13:8)

Άγιοι Ορθοδόξων Εκκλησιών εκτός Ελλάδος

Moderator: inanm7

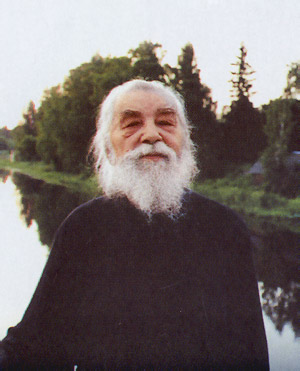

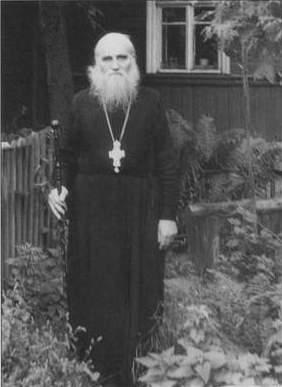

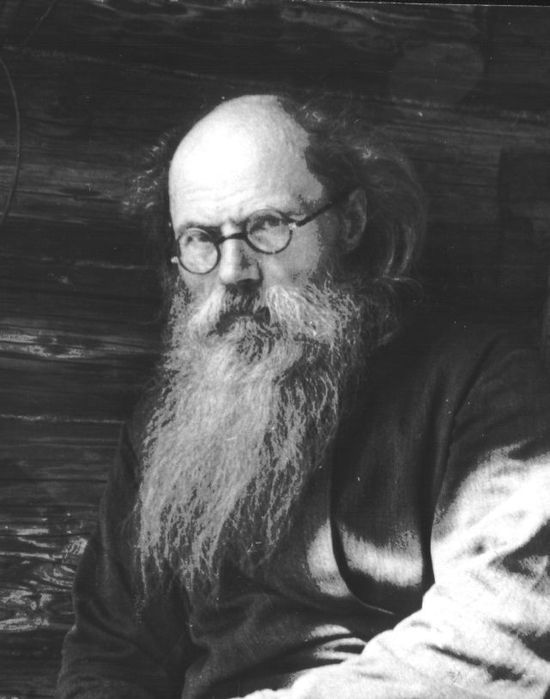

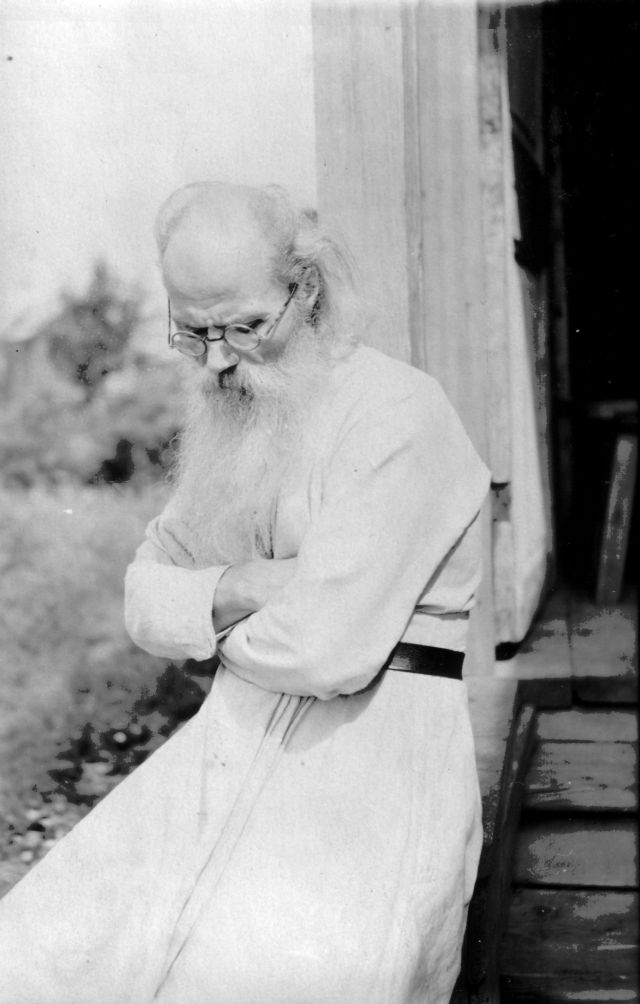

archimandritis Ιωάννης Κρεστιάνκιν

Δυστυχώς, το αγγλικό κείμενο.

ARCHIMANDRITE IOANN,

THE ELDER OF PSKOV-CAVE MONASTERY, REPOSED IN THE LORD

Pskov Cave Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos, February 5, 2006

On February 5, the day of All Russian New Martyrs and Confessors, the oldest monk and spiritual father of the Pskov Cave Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos, greatly loved Elder Archimandrite Ioann (Krestiankin), reposed in the Lord. He was 95 years old. Father Ioann passed away a few minutes after taking Holy Communion.

Father Ioann is known and revered in many countries of the world. It is impossible to convey what Father Ioann meant for his spiritual children and for all of the Russian Orthodox Church. In the last years, due to his age and poor health, he did not have an opportunity to receive all those who needed his advice. However letters for him from many parts of the world keep coming to Pskov Cave monastery. Father Ioann’s sermons and books keep opening a new, spiritual world for thousands of people and bring yearning souls to God. Among the most famous and popular books of his talk and letters are "The Experience of Preparing a Confession�, "Sermons, Thoughts and Congratulations�, "Reference Book for the Monastics and Laymen� and the compilation "Letters of Archimandrite Ioann (Krestiankin)�. Sermons and letters by Father Ioann have been translated into foreign languages and published abroad.

On April 11, 1910, in the town of Orlov an eighth child was born in the family of Mikhail Dmitrievich and Elizaveta Illarionovna Krestiankins. The boy was christened Ioann after Saint Ioann of Desert, whose memory was remembered that day. It is remarkable that the memory of Saint Venerable Mark and Jona of Pskov Cave monastery was celebrated the same day as well. Ivan helped at the church, throughout services since he was a little boy. Later in Orlov he became a postulant under the guidance of Archbishop Seraphim (Ostroumov), who was well-known for his strictness, When Ivan turned two, his father, Mikhail Dmitrievich, died. His highly devout and religious mother, Elizaveta Illarionovna, brought him up on her own.

Father Ioann has always gratefully remembered those who led him on his spiritual path. In his childhood in Orlov he was directed by archpriests Father Nikolai Azbukin and Father Vsevolod Kovrigin. When he was ten years old he was influenced by archpriest-staretz (spiritual Elder) Georgy Kosov from the village of Spas-Chekriak in Orlov region. Father Georgy was a spiritual disciple of Venerable Amvrosy of Optinsky monastery.

As a young man Father Ioann first learnt about his future monastic mission from his two friends, a future Martyr Archbishop Seraphim (Ostroumov) and Bishop Nikolai (Nikolsky). A nun-staritsa from Orlov, Vera Alexandrovna Loginova, when giving Father Ioann her blessing to live in Moscow, told him she would meet him in the land of Pskov in the distant future.

After finishing school Ivan Krestiankin did a book-keeping course and worked as an accountant having moved to Moscow. On January 14, 1945 at the Vagankovski cemetery’s church he was ordained deacon by Metropolitan Nikolai (Jarushev). The same year, on the day of Jerusalem icon of the Mother of God, October 25, he was ordained priest by Patriarch Alexy I. It was at the parish of the Nativity of Christ in Izmailovo, and he was left to serve there.

Father Ioann did an external Seminary degree and in 1950, having studied for four years at Moscow Theological Academy, he finished his PhD dissertation. But he had no chance to get the recognition of his work, because he was arrested for his zealous pastoral service at the end of April 1950. His verdict was seven years of labour camps. He was freed two years early, in February 1955 and was stationed in Pskov diocese, and in 1957 was sent to Riazan diocese where he served as a priest for nearly eleven years.

The young priest was ministered by the Spiritual Elders of Glinsk, and one of them, Schema-archimandrite Seraphim (Romantsev) became his spiritual father, and later received the monastic vows of his spiritual child. The last Elder of Optina Hegumen Ioann (Sokolov) saw a spiritual soul mate in an ordinary parish priest. Father Ioann was tonsured to monastic orders in Sukhumi on June 10, 1966, the day of Saint Sampson.

On March 5, 1967 hieromonk Ioann was admitted to Pskov-Cave monastery. He was consecrated Hegumen on April 13, 1970 and consecrated Archimandrite on April 7, 1973.

Father Ioann was taught by the monastic daily life itself and by the real people who were the devout monks of Pskov-Cave monastery: Hieroschemonk Simeon (Zhelnin), Schema-archimandrite Pimen (Gavrilenko), Archimandrite Afinogen (Agapov), abbot Archimandrite Alipiy (Voronov); also the last Valaam Elders: Hieroschemonk Mikhail (Pitkevich), Schehegumen Luka (Zemskov), Schemonk Nikolai (Monakhov), and retired Archbishops: Bishop Feodor (Tekuchev) and Metropolitan Veneamin (Fedchenkov).

Father Ioann himself suffered for his faith, having gone through prison camps, so his decease on the day of commemorating New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia is not a coincidence. We believe that having joined the other venerable souls he will face the Lord’s throne with heartfelt prayers for us.

Father Ioann will forever remain in the memory of all who knew him as a wise priest, to whom the Lord’s will was opened, who was a diligent monk, fasting and praying hard, who shared generously his rich life experience and warmed with his love everyone who turned to him for advice, and who was a worthy successor of the monastery’s tradition of Elders.

May his memory be eternal!

MAY GOD GIVE YOU WISDOM!

A LETTER OF FR. JOHN KRESTIANKIN

Be the salt of the earth

Pray to the Holy Martyr Tryphon, and through his intercessions you will always have work. Go to church to pray, and help whomever you can, but your main work should be your occupation in the world.

Believers should be the salt of the earth, and not close themselves up to people. Preach not so much with words as with your life, your patience and love towards suffering and lost people.

Do not look too far ahead, and if you will live every day with God and with prayer, the Lord will draw your little boat through life and direct it toward salvation.

May the Lord preserve you and make you wise!

http://www.bath-orthodox.org.uk/html/fr__ioann_krestiankin.html

ARCHIMANDRITE IOANN,

THE ELDER OF PSKOV-CAVE MONASTERY, REPOSED IN THE LORD

Pskov Cave Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos, February 5, 2006

On February 5, the day of All Russian New Martyrs and Confessors, the oldest monk and spiritual father of the Pskov Cave Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos, greatly loved Elder Archimandrite Ioann (Krestiankin), reposed in the Lord. He was 95 years old. Father Ioann passed away a few minutes after taking Holy Communion.

Father Ioann is known and revered in many countries of the world. It is impossible to convey what Father Ioann meant for his spiritual children and for all of the Russian Orthodox Church. In the last years, due to his age and poor health, he did not have an opportunity to receive all those who needed his advice. However letters for him from many parts of the world keep coming to Pskov Cave monastery. Father Ioann’s sermons and books keep opening a new, spiritual world for thousands of people and bring yearning souls to God. Among the most famous and popular books of his talk and letters are "The Experience of Preparing a Confession�, "Sermons, Thoughts and Congratulations�, "Reference Book for the Monastics and Laymen� and the compilation "Letters of Archimandrite Ioann (Krestiankin)�. Sermons and letters by Father Ioann have been translated into foreign languages and published abroad.

On April 11, 1910, in the town of Orlov an eighth child was born in the family of Mikhail Dmitrievich and Elizaveta Illarionovna Krestiankins. The boy was christened Ioann after Saint Ioann of Desert, whose memory was remembered that day. It is remarkable that the memory of Saint Venerable Mark and Jona of Pskov Cave monastery was celebrated the same day as well. Ivan helped at the church, throughout services since he was a little boy. Later in Orlov he became a postulant under the guidance of Archbishop Seraphim (Ostroumov), who was well-known for his strictness, When Ivan turned two, his father, Mikhail Dmitrievich, died. His highly devout and religious mother, Elizaveta Illarionovna, brought him up on her own.

Father Ioann has always gratefully remembered those who led him on his spiritual path. In his childhood in Orlov he was directed by archpriests Father Nikolai Azbukin and Father Vsevolod Kovrigin. When he was ten years old he was influenced by archpriest-staretz (spiritual Elder) Georgy Kosov from the village of Spas-Chekriak in Orlov region. Father Georgy was a spiritual disciple of Venerable Amvrosy of Optinsky monastery.

As a young man Father Ioann first learnt about his future monastic mission from his two friends, a future Martyr Archbishop Seraphim (Ostroumov) and Bishop Nikolai (Nikolsky). A nun-staritsa from Orlov, Vera Alexandrovna Loginova, when giving Father Ioann her blessing to live in Moscow, told him she would meet him in the land of Pskov in the distant future.

After finishing school Ivan Krestiankin did a book-keeping course and worked as an accountant having moved to Moscow. On January 14, 1945 at the Vagankovski cemetery’s church he was ordained deacon by Metropolitan Nikolai (Jarushev). The same year, on the day of Jerusalem icon of the Mother of God, October 25, he was ordained priest by Patriarch Alexy I. It was at the parish of the Nativity of Christ in Izmailovo, and he was left to serve there.

Father Ioann did an external Seminary degree and in 1950, having studied for four years at Moscow Theological Academy, he finished his PhD dissertation. But he had no chance to get the recognition of his work, because he was arrested for his zealous pastoral service at the end of April 1950. His verdict was seven years of labour camps. He was freed two years early, in February 1955 and was stationed in Pskov diocese, and in 1957 was sent to Riazan diocese where he served as a priest for nearly eleven years.

The young priest was ministered by the Spiritual Elders of Glinsk, and one of them, Schema-archimandrite Seraphim (Romantsev) became his spiritual father, and later received the monastic vows of his spiritual child. The last Elder of Optina Hegumen Ioann (Sokolov) saw a spiritual soul mate in an ordinary parish priest. Father Ioann was tonsured to monastic orders in Sukhumi on June 10, 1966, the day of Saint Sampson.

On March 5, 1967 hieromonk Ioann was admitted to Pskov-Cave monastery. He was consecrated Hegumen on April 13, 1970 and consecrated Archimandrite on April 7, 1973.

Father Ioann was taught by the monastic daily life itself and by the real people who were the devout monks of Pskov-Cave monastery: Hieroschemonk Simeon (Zhelnin), Schema-archimandrite Pimen (Gavrilenko), Archimandrite Afinogen (Agapov), abbot Archimandrite Alipiy (Voronov); also the last Valaam Elders: Hieroschemonk Mikhail (Pitkevich), Schehegumen Luka (Zemskov), Schemonk Nikolai (Monakhov), and retired Archbishops: Bishop Feodor (Tekuchev) and Metropolitan Veneamin (Fedchenkov).

Father Ioann himself suffered for his faith, having gone through prison camps, so his decease on the day of commemorating New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia is not a coincidence. We believe that having joined the other venerable souls he will face the Lord’s throne with heartfelt prayers for us.

Father Ioann will forever remain in the memory of all who knew him as a wise priest, to whom the Lord’s will was opened, who was a diligent monk, fasting and praying hard, who shared generously his rich life experience and warmed with his love everyone who turned to him for advice, and who was a worthy successor of the monastery’s tradition of Elders.

May his memory be eternal!

MAY GOD GIVE YOU WISDOM!

A LETTER OF FR. JOHN KRESTIANKIN

Be the salt of the earth

Pray to the Holy Martyr Tryphon, and through his intercessions you will always have work. Go to church to pray, and help whomever you can, but your main work should be your occupation in the world.

Believers should be the salt of the earth, and not close themselves up to people. Preach not so much with words as with your life, your patience and love towards suffering and lost people.

Do not look too far ahead, and if you will live every day with God and with prayer, the Lord will draw your little boat through life and direct it toward salvation.

May the Lord preserve you and make you wise!

http://www.bath-orthodox.org.uk/html/fr__ioann_krestiankin.html

- Georgios Rossos

Re: archimandritis Ιωάννης Κρεστιάνκιν

Δεν πειράζει αδελφέ μου,καλώς μας ήρθες και keep posting.Υπάρχουν αρκετοί που μας διαβάζουν και θα τους ήταν ευκολότερο να διαβάζουν στ'αγγλικά.

Ιn English:Welcome my brother is Jesus Christ and keep posting!There are many other people from abroad who are reading us and it would be easier for them to read in English.Thank you!

Ιn English:Welcome my brother is Jesus Christ and keep posting!There are many other people from abroad who are reading us and it would be easier for them to read in English.Thank you!

Last edited by Matina on Fri Nov 18, 2011 10:28 pm, edited 1 time in total.

O Κύριός μου κι ο Θεός μου!

-

Matina - Posts: 2161

- Joined: Tue Nov 15, 2011 10:36 am

Re: archimandritis Ιωάννης Κρεστιάνκιν

CHRIST IS RISEN!

Now all things are filled with light; heaven and earth, and the nethermost parts of the earth… Christ is Risen!

Children of God! From a fullness of unearthly joy I greet you with words full of Divine power: “Christ is Risen!” The holy fire of this salvific tiding has burst anew with bright flames over the Lord’s Tomb, and has spread throughout the world.

The Church of God, filled with the light of this fire, gives it to us: “Christ is Risen!”

Beloved in Christ brethren and sisters, my friends! You of course will have noticed that, of all our great and joyful Christian feasts, the feast of the Luminous Resurrection of Christ is characterized by a special solemnity, a special joy: it is the feast of feasts and the festival of festivals!

No service in our Orthodox Church is more magnificent, more heartfelt, than Paschal Matins. Therefore all the faithful rush to God’s church on the Paschal night. Indeed, the Paschal Divine service resembles a magnificent banquet prepared by the Lord for all those who stream under the grace-filled protection of His House.

Contemplate the contents of St John Chrysostom’s “catechetical homily”! With paternal tenderness and cordiality the Lord accepts those who love Him with all their being. “Blessed is he who has wrought from the first hour” – these are those who from their youth undeviatingly follow His Divine steps.

Yet he does not reject those who, overcoming doubt in their souls, approach God only in their mature or even elderly years. “Let him not fear for having delayed, for the Lord in His love will accept the last even as the first, accepting the deeds and welcoming the intention.”

Undoubtedly all who were in church on the Paschal night experienced an unusual delight… Our souls rejoiced, filled with a sense of gratitude to our Lord and Savior for the eternal life He has given us all. Indeed, Christ’s Resurrection raised the human race from earth to Heaven, giving an elevated and noble meaning to human existence.

The human soul yearns for the eternal life of joy. It seeks it… Therefore people rush to the luminous Matins in God’s church. And not only the faithful, but even those whose consciousness is from the Christian religion.

They come here not simply to look at the solemnity of the Christian service. Their souls, given by God to everyone at birth, are attracted to the light of the inextinguishable Sun of Truth, seeking the truth.

Faithful people on this holy night feel an abundant outpouring of the luminous joy of Christ’s Resurrection with particular power. And no wonder! Christ’s Resurrection is the foundation of our faith, the inviolable pillar of our earthly life.

By His Resurrection, Christ has given to people to comprehend the truth of His Divinity, the truth of His elevated teaching, the salvific nature of His death. Christ’s Resurrection is the completion of His earthly deed [podvig]. There could not have been any other end, for this was the direct consequence of the moral sense of Christ’s life.

If Christ be not risen, the Apostle Paul writes, then our preaching is in vain and our faith is futile. But Christ is risen, and He has raised all mankind with Him!

The Savior brought perfect joy to people on earth. Therefore on the Paschal night we hear a hymn that we ourselves take part in: “Angels in the heavens, O Christ our Savior, praise Thy Resurrection with hymns; deem us also who are on earth worthy to glorify Thee with a pure heart.”

In His prayer before His suffering on the Cross, He asked His Heavenly Father for the gift of this great joy for people: Sanctify them by Thy truth… that they might have My joy fulfilled in themselves (Jn 17:17, 13).

Through the Resurrection of Christ, a new world of holiness and true blessedness has been opened unto man.

During His earthly life the Savior repeatedly pronounced words that are precious to the faithful soul: Because I live, ye shall live also (Jn 14:19); My peace I give unto you (Jn 14:27); These things have I spoken unto you, that My joy might remain in you, and that your joy might be full (Jn 15:11).

The Apostle Paul, in his Epistle to the Romans, writes: For if we have been planted together in the likeness of His death, we shall be also in the likeness of His resurrection… Now if we be dead with Christ, we believe that we shall also live with him (Rom 6:5, 8).

A new life has been opened unto man. He has been given the possibility to die to sin in order to be raised with Christ and live with Him.

“A Pascha that hath opened the gates of Paradise to us,” we sing in the Paschal canon.

There is no joy, my beloved, more luminous than our Paschal joy. For we rejoice that, in the Resurrection, our eternal life has been opened unto us.

Our Paschal joy is joy for the transfiguration (change) of our life into an incorrupt life, in our aspiration for imperishable good, an incorruptible beauty. We now celebrate the greatest mystery, the Resurrection of Christ, the defeat of the Life-giver over death! Our Savior triumphed over evil and darkness, and therefore the Paschal Divine service of our Orthodox Church is so jubilant and joyful.

The faithful awaited this solemn service, preparing themselves for it during the long weeks of the Holy Forty Days. It is natural that their hearts are now filled with inexpressible joy.

The deepest meaning of Christ’s Resurrection is in the eternal life that He gave to all His followers. For 2000 years already His followers have unwaveringly believed not only that Christ arose, but in their own coming resurrection to eternal life.

Christ the Savior spoke many times during His earthly life about Himself as the bearer of life and resurrection. But then these words of the Divine Teacher were incomprehensible not only to the people who listened to Him, but even to His disciples and apostles.

The meaning of these words became clear only after Christ’s Resurrection. Only then did His apostles and disciples understand that He is, indeed, the Lord of life and the Conqueror of death. And then they went to preach throughout the entire world.

We, beloved, great each other during these joyful days with the words “Christ is Risen!” We will continue to greet one another in this way for the course of forty days, until the day of the Lord’s Ascension.

Just two words! But these are marvelous words, expressing unwavering faith, which gives joy to the human heart, in the truth of our immortality.

Christ is Life!

He many times spoke of Himself as the bearer of life and resurrection, as the source of eternal life, which is without end for those who believe in Him.

Christ is Risen! – and may our souls rejoice in the Lord.

Christ is Risen! – and may our fear of death vanish.

Christ is Risen! – and our hearts are filled with the joyful faith that we, too, will rise with Him.

To celebrate Pascha – this means to know with all one’s heart the power and grandeur of Christ’s Resurrection.

To celebrate Pascha – this means to become a new person.

To celebrate Pascha – this means with all one’s heart and mind to thank and glorify God for His ineffable gift, the gift of resurrection and love.

In these days we all exult and joyfully celebrate, praising and glorifying the deed [podvig] of the triumph of Divine love.

Christ is Risen!!!

Let us throw open our hearts to meet Him Who suffered, and died, and arose for our sake. He will enter and fill our life with Himself and His Light, transfiguring our souls. We answer this by striving towards Him along our way of the Cross, for at its end, there is no doubt, shines our own resurrection to life eternal.

http://sowingseedsoforthodoxy.wordpress.com/2011/04/26/bright-tuesday-fr-john-krestiankin/

- Georgios Rossos

Re: archimandritis Ιωάννης Κρεστιάνκιν

About Archimandrite John Krestiankin

On February 5, 2006, Russia's beloved elder, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), reposed in the Lord. The Pravdoliubov family, full of priests and even new martyrs, lived in Ryazan Province, where Fr. John served for many years in various parishes. This family has produced even more priests, one of whom serves in the Resurrection Church in Moscow, and has written his recollections of a life-long relationship with the wise spiritual instructor.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin).

For a long time, I did not write my recollections of Fr. John (Krestiankin). It seemed to me that everyone was writing their own. I thought, they will write everything they can! But when I read what many people really did write, I also wanted to write—especially since throughout many years of hearing confessions, I often cited Fr. John's opinion on the most varied issues.

I worked on my recollections throughout Great Lent of 2005, finished them on Pascha, and sent them to Pechory. Fr. John read these notes and approved them. He did not ask that anything be removed, had no problems with them, and now these notes are very, very dear to me. After all, Fr. John read them himself, and agreed with everything! He did not say that I wrote anything from my own self…

Thus, these recollections are valuable no matter how they have been written in that Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) himself approved of them.

* * *

My parents, Archpriest Anatoly and Olga Mikhailovna Pravdoliubov, were always very close to Fr. John (Krestiankin). When Fr. John served in the village of Troitsa-Pelenitsa (Yasakovo) in Ryazan diocese, my father was serving during those years in the town of Spassk-Ryazansky. These parishes were very close to each other and my parents often visited with Fr. John. Even then, they related to him as to an elder, although Fr. John was only four years older than my father. They were especially close during the time that Fr. John served at his last parish in Ryazan diocese—the St. Nicholas Church in the town of Kasimov. We children also remember that time well, for we were already sufficiently grown. We remembered the long Church services Fr. John served—All-Night Vigil with a litya, akathists, and very long sermons.

Fr. John did not serve in Kasimov very long, we remember that time as a great and significant period in our lives. I can explain this by saying that for Fr. John himself, every day was very important, and therefore people around him perceived time differently. A multitude of events fit into that short period of time: services, sermons, Fr. John's travels, after which he would always organize meetings where his close friends would gather with him: my parents and all the children, my uncle, Archpriest Vladimir Pravdoliubov and his family; and these talks would go on deep into the night. For the children, these were very important meetings—we were witnesses of the talks between clergymen, their discussions of pastoral problems, and questions regarding Church services.

At one of these meetings, Fr. John somehow mentioned monasticism. He was addressing my aunts, Vera Sergeyevna and Sophia Sergeyevna, as if urging them to think about receiving the monastic tonsure. Fr. John was not a monk before he moved to Pechory, and Vera Sergeyevna thought to herself, "And what is Fr. John? 'Grayish?' After all, he is not a monk!" Suddenly Fr. John turned to Vera Sergeyevna and said with a smile, "I'm grayish, grayish! Well, you also remain grayish for now."

Fr. John had a subtle sense of humor. Once after the Vigil service, he gave a very long sermon that lasted an hour and a half. When he had finished, he came up to the choir and asked, "Has anyone fallen out of the window?" My aunt Sophia Sergeyevna replied immediately, "What, is it already midnight?" Fr. John liked her answer.

In Kasimov, Fr. John began to serve the sacrament of Unction for all who wanted it. This had never been done before; Unction was considered a sacrament to be served only in case of serious illness. Fr. John agreed with this understanding of the sacrament, but persuaded my father, Archpriest Anatoly, and my uncle, Archpriest Vladimir, for a long time that such a time has come when no one can consider himself completely healthy—everyone has some kind of illness. Therefore, everyone can receive Unction once a year; and an announcement should be made in the church ahead of time so that everyone who wants to could come at the appointed time. Archpriests Anatoly and Vladimir agreed with Fr. John; nevertheless the Unction services at first took place not in the church, but at the home of my grandmother, Lydia Dimitrievna. This happened in February of 1967.

Two families gathered: that of Fr. Anatoly and of Fr. Vladimir. There were children and the elderly. The sacrament was served by Fr. John, my father and my uncle. They anointed everyone in order, and the priests anointed each other. After some time, the sacrament was served in the St. Nicholas Church, and then it was served yearly. I do not know how it was in other places, but this tradition gradually became widespread.

As for the allowed frequency of receiving Holy Communion, Fr. John said that everyone may receive once a month. He only blessed certain people to receive once every two weeks. I never heard of him blessing anyone to receive more often than that.

About confession, Fr. John said that in our time, both detailed and brief confessions are allowable. During the fasts, when there are great multitudes of people wishing to confess and receive the Holy Mysteries of Christ, there simply is no time for a detailed confession. When there is time, one should confess in detail; and when the time is short, there is nothing wrong with having a brief confession.

Fr. John left Kasimov on the second day of the feast of the Meeting of the Lord, on February 16, 1967, but we did not lose contact with him. Fr. John entered the Pskov-Caves Monastery [in Pechory, Pskov Province] as a monk—he had received the tonsure just before from Schema-Archimandrite Seraphim (Romanstov; canonized in 2010). I saw Fr. John in a klobuk and mantia for the first time when I came to visit him in the monastery. We children of Fr. Anatoly Pravdoliubov began visiting Pechory very often in order to receive Fr. John's blessing, hear his spiritual instructions, and pray at the monastery services.

The town of Pechory is located at such northern latitude that during the late spring and early summer, there are true "white nights," and during the winter, it is constantly dark. It would get light out by about 10:00 a.m., and by 4:00 p.m. it would be dusk. Thus, we would be going to church in the dark mornings, and by the evening services, it would almost be the dark of night. The number of pilgrims to the monastery greatly increased after Fr. John entered it. When we came to the monastery during the summertime, we would always meet some acquaintance there, either from Ryazan Province or from Moscow. There were significantly fewer pilgrims during the winter, and so we especially liked to go to Pechory during wintertime.

The train from Moscow arrived at the Pskov-Pechory station very early—at about five o'clock in the morning. The first bus that took people to the town would already be standing by the train station, and would depart while the train was still standing at the station. After Moscow life, people would find themselves in another world: quiet, white snow, frost, sidewalks sprinkled with sand and not salt as they were in Moscow. They would walk up to the monastery, the great gates of which would be yet closed. All would be silent, no one wanted to talk; they would wait until the monk-gatekeeper would open the gates. High above the gates hung a large icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, and a red icon lamp always burned before it. Finally, the monastery gates would slowly open and the pilgrims would enter the monastery grounds, one-by-one. Upon entering, they would make the sign of the cross, bow, and pass under the stone archway of the St. Nicholas church "over the gates," from whence began the "Bloody Path"[1] to the ancient church of the Dormition of the Mother of God, built into the caves. There, the brothers' moleben was about to begin. In the darkness of early morning, the figures of the monks could be seen hastening to the start of the moleben.

At that time in the Dormition Church, it was always dark. Only the icon lamps burned; even the candles on the candle stands would not yet be lit. That was the accepted order in the monastery, so that the brothers' moleben and midnight office would be served in the natural light of the lamps. The most important part of the moleben was the reading of the Gospel, Mt. 11:27–30: All things have been delivered to Me by My Father… Especially penetrating and meaningful sounded the words: Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. 30 For My yoke is easy and My burden is light. At the midnight office, of course, the most meaningful chant was the song, "Behold, the Bridegroom cometh at midnight…" The monks would be standing in the total darkness, in stately rows, before the icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, the main holy shrine of the monastery, and sing simply, without haste, "The Bridegroom cometh at midnight, and blessed is that servant whom He shall find watching. But unworthy is he whom He shall find in slothfulness…" It seemed that the monks were contemplating these words rather than singing them. Fr. John never missed the brothers' moleben, and his voice could always be distinguished in this simple choir of monastery brethren.

After the moleben, Fr. John would go into the altar and stand before the table of oblation. He would remove particles of the prosphora to commemorate a multitude of people—those he knew and those who asked for his prayers. He would do this only up to the Cherubic Hymn, before which he would leave the table of oblation and no longer remove the particles. One day, he shared with us the feelings that he experienced during his prayers for people—the living and the reposed. He said, "It is as if people are walking past me; the closer it gets to the Cherubic Hymn, the faster they want to go past. They hurry each other along, as if pushing each others' shoulders, so that I can commemorate them in time…"

Our trips to Pechory became a necessity for us, and our parents only welcomed their children's initiative to go to the monastery, and to receive Fr. John's blessing for every important life step.

Fr. John blessed me for army service with an icon of St. Sergius of Radonezh. I also received his blessing before entering the seminary. When Fr. John blessed me, he said, "Enter the seminary, and then the Theological Academy." When I was already working on my dissertation, Fr. John blessed me with an icon of the Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian. The theme of my dissertation was very complicated—theological, Christological; and by blessing me with the icon of St. John the Theologian, Fr. John gave me to know that I would be able to tackle it.

When the time came for me to marry, my future wife, Liubov Dimitrievna, and I first went to see Fr. John, because we resolved to bind our lives together only if it be blessed.

Fr. John (Krestiankin).

We came to Fr. John and told him about our intention. Fr. John told us, "Today, after the evening service in the Dormition Church, there will be a monastic tonsure. Come and pray, and then we will decide whether you should take the tonsure, or enter into marriage."

You can imagine what feelings we took away from our meeting with Fr. John. For a whole twenty-four hours, we did not know what the answer would be, and in the evening we prayed in the Dormition Church, as Fr. John had told us to do. The monastic tonsure was performed in almost total darkness. Candles and icon lamps flickered, and the monks quietly sang, "In the Fatherly embrace..." The monk receiving the tonsure crawled along the stone floor in a long white gown, while the hieormonks and archimandrites, including Fr. John, covered him with their mantias. It was both solemn and sad. After the tonsure, we went back to the house where we were staying, and only the next evening were we with Fr. John again.

Without asking us anything, he blessed us for marriage with the icons of the Savior Made-Without-Hands and the "Jerusalem" Mother of God. We received invaluable instructions from him then. Fr. John talked about marriage as a sacrament, and said words that we have remembered all our lives. "A family is a domestic church," said Fr. John. "You should always have before your mental gaze the following picture: the icon of the Savior, the marriage bed, and the infant's cradle. Marriage is a sacrament. And what a miracle is the birth of children! "O Lord, Thou hast seen how my flesh was woven!" he cited from one of the psalms in the Russian translation.

Fr. John said that love never disappears in a Christian marriage; to the contrary, it grows more and more with every year, and the longer the spouses live together, the more they love each other.

I received Fr. John's blessing to become a deacon. At that time, I was subdeacon to His Holiness Patriarch Pimen. Having blessed me, Fr. John said, "Be in obedience to His Holiness the Patriarch: as he says, so let it be." I waited a rather long time… Finally, one day, after the Vigil in the Elokhov Cathedral,[2] when the curtain [on the royal doors] had already been drawn shut, I heard His Holiness Patriarch Pimen call me to his patriarchal place on the right side of the holy table, and then he said, "I am going to ordain you tomorrow." So, on Sunday, the fifth week of Great Lent, on the day of St. Mary of Egypt—April 1, 1979—His Holiness Patriarch Pimen ordained me a deacan and appointed me to serve in the church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul in Lefortovo.[3]

When I told Fr. John about this, he remembered the years of his imprisonment. "In 1950, I was imprisoned in Lefortovo prison," he said. Everyone who was with me in the prison cell could hear the ringing of the bells at the Sts. Peter and Paul Church. It is located near the prison; we would always know when important moments in the services were occurring, and we would pray especially fervently at that time."

After I had been ordained, I would come to the Pskov-Caves Monastery and serve with the monks… Sometimes I would be able to serve with Fr. John. This was a great consolation. One day, I served with Fr. John at the parish in the village of Yushkovo.

It was on the feast of St. Elias—the patronal feast of the parish. The church with the houses near it more resembled a monastery skete than a parish church. Fr. Paisy served there. He was a monk. Several elderly nuns lived at the church. Fr. Paisy always invited Fr. John to serve with him on that day, and Fr. John accepted his invitation for many years. Yushkovo is located about fifteen to twenty kilometers from Pechory, and therefore, having arrived that morning from Moscow, I was able to get to the church before the service started. When Fr. John saw me in the altar, he was very amazed, and asked, "How did you get here?" "I came especially to pray with you," I answered. "Will you serve?" asked Fr. John. "If you bless, I will," I said. "Definitely, serve!" said Fr. John.

That was a wonderful day! Before the beginning of the Liturgy, Fr. John served a moleben with an akathist to the Prophet Elias and a blessing of the waters. There were people near him, and everyone sang. After the Liturgy was a cross procession with a sprinkling of the people and the church. It was as if Fr. John was again serving in a parish. He talked with people, whole groups and families coming up to him. This was all at the parish, amidst the grasses and trees. The sun was shining, and it was very warm outside—the very height of summer! After the service and procession ended, Fr. John went to sprinkle the parish buildings with holy water. "Let's go, we'll sprinkle Maria's hut with holy water," he said, referring to the tiny house more resembling a hut that a house. Everyone had joyful smiles on their faces, and Nun Maria was simply elated that Fr. John had come to her house to sprinkle it with holy water.

Then there was a meal in Fr. Paisy's house. Again Fr. John talked with people, and there were very interesting conversations. One of the priests asked Fr. John if the Chernobyl catastrophe was apocalyptic, and could Chernobyl have been that very "Wormwood" cited in the book of Revelations? "I would not call that accident at the nuclear power plant a direct fulfillment of the Apocalypse," replied Fr. John. "One must relate very cautiously to any explanation of the book of Revelations, and there is a reason why the Church does not accept very many of the explanations regarding it. There is an explanation of the book of Revelations by St. Andrew of Cesarea—it is accepted by the Church, and it may be read. All the rest are very doubtful!" Fr. John also talked about how very bad it is when Church books and icons are sold in ordinary stores, next to very different products. "This should not be!" he said. He also said that every person should have a close connection with his guardian angel. In a word, the subjects of conversation were quite varied. Unfortunately, however, they did not last very long—Fr. John had to go back to the monastery.

A car was waiting for Fr. John at the foot of the hill on which the church stood—a "Volga," which Fr. Paisy had reserved earlier. We all descended the hill to that car, and Fr. John went up to the young driver and gave him a piece of candy. "No, thank you," the driver answered. Fr. John exclaimed, "What self-restraint!" There happened to be another car next to the "Volga"—a "Niva." The priest who had arrived in it drew Fr. John over to the car, asking him to go with him instead. "Where is your travelling companion, the tall, young man?" Fr. John inquired, because everyone had seen that priest in the church during the service, surrounded by a whole group of his parishioners. "There he is!" said batiushka, and opened the trunk of the Niva. In the trunk was a man, about thirty years old and two meters tall, literally doubled over. The priest had stuffed him in there in order to make room for Fr. John. "Have you no conscience?! What are you doing?! How could you treat a man like that?!" Fr. John said sternly. "I will not go with you!" He then instructed me to be seated in the back of the Volga, sat down next to me, and we drove back to the monastery, continuing our discussion.

The next day, that priest saw me in the monastery and said, "how I envy you: you drove together with Fr. John!"

Around the mid 1980's, the first confusion over the [social security] numbers started. At that time, it was not SSNs, but the new pension documents. People had to fill out some forms that required them to write a specific number, each form having its own. People started talking about the seal of Antichrist, and the unacceptability of such forms. People were always asking me how to relate to them. I considered that there wasn't anything particularly wrong with them, but I decided to ask the opinion of Fr. John. On one of my trips to Pechory, I told Fr. John in detail all about the people's concerns. Fr. John answered me personally in the following way. We must not fear any numbers. Numbers are everywhere: there are digits on watches, on documents, on the pages of books. We should instead fear the sins that we commit, and especially the temptations of these times. If we easily give in to these temptations, if we easily sin, then the spirit of antichrist is working in us, and the seal of antichrist could already be upon us, unnoticeably even to ourselves!

When the confusion over the SSNs arose, I asked him about this as well. Fr. John answered that everything he had said regarding the pension documents is applicable also to SSNs: we don't need to be afraid of any numbers!

I served in the church of Sts. Peter and Paul for a long time—eleven whole years. I became an Archdeacon, and served with a double orarion, but my desire was to serve in the priestly rank. I asked Fr. John several times for his blessing to submit a request to the Patriarch for ordination, but he answered, "The time has not yet come, it is still early." When they started calling me to Ryazan diocese, I went to get a blessing to transfer to that diocese. But Fr. John answered, "Under no circumstances! Stay where you are! You will be a priest. When the time comes, it will all happen by itself, without any requests! But for now, you shouldn't go looking for anything—that would be an asked-for cross, not your own, not from God, but from yourself. Over the course of twelve years, I was at six different parishes: Letovo, Nekrasova, Borets, Kasimov… but I never looked for anything. I was always transferred with various formulations: for the betterment of Church life, with regard to Church need… Never of my own asking! You, too—never go looking for anything; everything will come in its own time. By the way," added Fr. John, seeing my desire to transfer to another diocese, "You can do as you know best." "No, Fr. John, what are you saying?" I replied. "I will not take up anything without your blessing." It was obvious that Fr. John approved of this inclination [to follow his advice].

Several more years passed, and Fr. John said came to pass. In 1990, not long before our church's patronal feast—the Apostles Peter and Paul—I unexpectedly received an order from His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II stating that upon my ordination as a priest I am appointed to served in the church of the Resurrection of Christ in Solkolniki. On that same day, the feast on the Apostles Peter and Paul, the Patriarch came to our church and served a solemn Liturgy, at which he ordained me a priest. After the Liturgy, His Holiness said, "This is my first priestly ordination in Moscow." Truly, after his consecration as Patriarch on June 10, 1990, he had not yet ordained anyone.

I started serving right afterwards at my new position in Sokolniki, and at the first opportunity, I went to see Fr. John. I told him everything that had happened to me, and Fr. John congratulated me with my ordination into the priesthood, only approvingly nodding his head. He expressed his views in only a few words on everything I told him. When we went together to the service in the Dormition Church, Fr. John said to the priest who stood next to me in the altar, "Everything happens with Fr. Mikhail according to God's will. His guardian angel leads him by the hand."

By that time, for already a few years my parents were no longer among the living, and I always had filial feelings for Fr. John during those years. Especially now that I had come to him with news about my great joy at receiving the priestly ordination, I especially felt as if I had come to my own father.

My meetings with Fr. John usually took place in his cell. We would come to him at the appointed time, and the first thing he would do would be to stand before the icons[4] and read the prayer: "O Heavenly King," "When the Most High came down he confused the tongues, divided the nations; but when he parted the tongues of fire, he called all to unity, and with one voice we glorify the all-holy Spirit."[5] "We shall never cease to hymn Thy power, Most Holy Theotokos, unworthy as we are…" and we always understood that this was not just a conversation but a communion, in which we would hear instructions that we must fulfill. We knew that the answers to our questions to Fr. John would be an expression of God's will in our life. Not everyone has the happiness of being able to come to an elder, to ask him questions, receive specific answers (for example, about marriage), and be sure that this answer is God's will.

After praying, Fr. John would sit down on a small sofa. He would usually seat me to the left of himself, my eldest son, Seriozha to the right, and little Vanya would make himself at home on a small stool at his feet. Liubov Dimitrievna was always next to the youngest son, in front of Fr. John. No matter how much time would have elapsed since our last meeting with him, Fr. John always met us as if we had just seen each other recently. One day, after we had not seen each other for a rather long time, Fr. John said, "Old friends are getting together—I am very glad!" We would tell him about ourselves, and ask him questions. Fr. John always took a lively interest in everything: who is studying where, and who is doing what?

He would tell us about himself; at times relating how difficult it was for him. "I throw off sixty years from myself, and leave six," he once said to us.

He spoke about how important it is for a parish priest to relate to everyone equally, and never to allow any special feelings for one person or another. "Feelings are born in the head," he said, "they go down to the heart, and torment it."

When the time came for my eldest son to determine his path in life, Fr. John asked him, "Do you want to continue the work of your fathers?" "Yes, I do!" he answered fervently. "The priesthood is a calling," said Fr. John, and this was a blessing to our Seryozha for his whole life.

During the time we were expecting a child, Fr. John said to us, "You will have a boy. Call him John." Truly, a boy appeared in the world, and we called him John, in honor of Fr. John. We decided that his patron saint would be the Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian, and that his name day would be the same as Fr. John's—July 13, the Synaxis of the twelve apostles.

I asked Fr. John a question about spiritual fatherhood: how should one relate to the problem that comes up very acutely in many parishes everywhere—many priests who consider that they have a right to restrain their parishioners, and forbid them to confess to another priest.

Fr. John answered thus: "It is very important that all that comprises a person: reason, will, conscience, and spiritual freedom, not be violated. If they are violated, then sickness begins. As it is said in the Gospels, Christ healed the blind, the deaf, the lame, the lepers… (Fr. John paused and looked at me straight in the eye) and the demonized. Yes, that is also a sickness, a spiritual sickness. The beginning of that sickness is expressed in the fact that a person is deprived of his own will; he submits his will to another person. Then the conscience is almost in no state to speak to the person, it is silenced as the result of that person substituting his own responsibility before God with the responsibility of someone else."

"What is spiritual fatherhood?" continued Fr. John. "It is when a spiritually experienced elder has taken on spiritual children numbering no more than twelve. This is a spiritual fatherhood: when the elder literally feeds his children from his own hand, and passes them on to another in the case of his death. That is true spiritual fatherhood! But that cannot happen in our parishes. There should be total freedom there! Movement from one priest to another can occur for very different reasons. It could even happen because one priest has more time than another does. Why should I take the time of a terribly overburdened batiushka—it's better that I go to another one who is not so busy. One can then go to a less burdened priest without any confusion over it. Or, for example, a priest is transferred. Why should all his parishioners follow him to another parish? They should remain where they are and go to the priest who is serving with them, in the church that is near to home and is the parish of those people. I would always say to my parishioners when I was transferred, 'Stay where you are, do not run off anywhere, you now have a different batiushka. They are transferring me, and not you!' Otherwise, sometimes it happens that you say something at confession, and they answer you, 'My spiritual father blessed me to do this or that.' What spiritual father? Where is he, that spiritual father? It turns out that somewhere, far, far away, there is a batiushka, someone's spiritual father. Well, why? Why have these confusing complexities? You say in such cases, 'Do what you want!' Or it sometimes happens like this: people come to a priest and say, 'Batiushka, we have come to you for the last time—we are leaving you.' 'Well, go with God!' he answers them. That is how it should be!"

"Divisions into parishes have always existed. I remember it thus in Orel, where I spent my childhood," continued Fr. John. "But those divisions where first of all territorial. All of Orel was divided into distinct regions, which bound each person to his own church. Some streets were connected with one church, while other streets were connected to another church. The whole town was divided, and priests were not supposed to serve needs in a region that was not theirs. Pannikhidas, Communion, funerals, baptisms… every street knew its church. But people prayed wherever they wanted. It would even happen like this: before one Church feast or another, the priest would announce from the ambo that tomorrow, for example, is a certain feast, and we are all going to pray in some church he would name, where it they will celebrate their patronal feast. And all would go there. There should be division into parishes, but we all remain one whole Church, and we all raise our prayer to God as a united whole."

"Just as did His Holiness Patriarch Pimen," Fr. John once said, "I will say that the Church Slavonic language should always be used in our church services, as well as the old [Julian] calendar; and with Catholics, we can drink tea."

Archpriest Mikhail Pravdoliubov.

Archpriest Anatoly Pravdoliubov, my father, was very sick for a long time before his death. One day, when he was in a painful condition, he fell down and hurt himself badly. When I came to Fr. John and told him about it, he answered, "I will tell you about myself, how I also fell down one day. At one of my parishes, I was blessing a village home. I was walking through the house with a blessing brush in my hand, sprinkling the rooms with holy water, and did not notice that behind the curtain in one of them was an open trap door into the cellar. I took a step behind that curtain and did not even figure out immediately what happened: I had fallen into that cellar, ended up on its very bottom—on the earth. I lay there like that, spread out on the floor of the cellar, in my vestments, with the blessing brush and cross in my hands, like St. Nicholas as he is depicted on the icons. And it was alright! Even if a righteous man falls, he will remain whole," he quoted someone, and then added, "But that is not about us, not about us!" But I understood quite well that he was calling both himself and my father righteous men.

At the end of the 1980's, Fr. John talked about our times as about a time of bloodless martyrdom. "You are bloodless martyrs," he would say. And it will get even harder. Your time is harder than ours is, and one can only sympathize with you. But be brave and do not fear! Now there is confusion, turmoil, and muddle; and it will get even worse: perestroika, perestrelka, pereklichka [perestroika—change in the government, perestrelka—a shoot-out, and pereclichka—roll call]. The time is coming of serious spiritual famine, although the tables will be full."

Fr. John would also see us out with prayer. We would all arise and pray; Fr. John would take a brush and anoint each of us with oil from various holy places, then sprinkle each with holy water, give us a little to drink from a small silver cup that he always kept in his cell for this purpose, and then pour a little holy water on our chests. Then he would bless each of us, and we would depart from him with renewed spiritual strength.

Fr. John's love for God and all people passed on to us to a certain degree. That is why we always want to go to Pechory—to receive from Fr. John his grace-filled, prayerful help and blessing.

http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/44552.htm

On February 5, 2006, Russia's beloved elder, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin), reposed in the Lord. The Pravdoliubov family, full of priests and even new martyrs, lived in Ryazan Province, where Fr. John served for many years in various parishes. This family has produced even more priests, one of whom serves in the Resurrection Church in Moscow, and has written his recollections of a life-long relationship with the wise spiritual instructor.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin).

For a long time, I did not write my recollections of Fr. John (Krestiankin). It seemed to me that everyone was writing their own. I thought, they will write everything they can! But when I read what many people really did write, I also wanted to write—especially since throughout many years of hearing confessions, I often cited Fr. John's opinion on the most varied issues.

I worked on my recollections throughout Great Lent of 2005, finished them on Pascha, and sent them to Pechory. Fr. John read these notes and approved them. He did not ask that anything be removed, had no problems with them, and now these notes are very, very dear to me. After all, Fr. John read them himself, and agreed with everything! He did not say that I wrote anything from my own self…

Thus, these recollections are valuable no matter how they have been written in that Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) himself approved of them.

* * *

My parents, Archpriest Anatoly and Olga Mikhailovna Pravdoliubov, were always very close to Fr. John (Krestiankin). When Fr. John served in the village of Troitsa-Pelenitsa (Yasakovo) in Ryazan diocese, my father was serving during those years in the town of Spassk-Ryazansky. These parishes were very close to each other and my parents often visited with Fr. John. Even then, they related to him as to an elder, although Fr. John was only four years older than my father. They were especially close during the time that Fr. John served at his last parish in Ryazan diocese—the St. Nicholas Church in the town of Kasimov. We children also remember that time well, for we were already sufficiently grown. We remembered the long Church services Fr. John served—All-Night Vigil with a litya, akathists, and very long sermons.

Fr. John did not serve in Kasimov very long, we remember that time as a great and significant period in our lives. I can explain this by saying that for Fr. John himself, every day was very important, and therefore people around him perceived time differently. A multitude of events fit into that short period of time: services, sermons, Fr. John's travels, after which he would always organize meetings where his close friends would gather with him: my parents and all the children, my uncle, Archpriest Vladimir Pravdoliubov and his family; and these talks would go on deep into the night. For the children, these were very important meetings—we were witnesses of the talks between clergymen, their discussions of pastoral problems, and questions regarding Church services.

At one of these meetings, Fr. John somehow mentioned monasticism. He was addressing my aunts, Vera Sergeyevna and Sophia Sergeyevna, as if urging them to think about receiving the monastic tonsure. Fr. John was not a monk before he moved to Pechory, and Vera Sergeyevna thought to herself, "And what is Fr. John? 'Grayish?' After all, he is not a monk!" Suddenly Fr. John turned to Vera Sergeyevna and said with a smile, "I'm grayish, grayish! Well, you also remain grayish for now."

Fr. John had a subtle sense of humor. Once after the Vigil service, he gave a very long sermon that lasted an hour and a half. When he had finished, he came up to the choir and asked, "Has anyone fallen out of the window?" My aunt Sophia Sergeyevna replied immediately, "What, is it already midnight?" Fr. John liked her answer.

In Kasimov, Fr. John began to serve the sacrament of Unction for all who wanted it. This had never been done before; Unction was considered a sacrament to be served only in case of serious illness. Fr. John agreed with this understanding of the sacrament, but persuaded my father, Archpriest Anatoly, and my uncle, Archpriest Vladimir, for a long time that such a time has come when no one can consider himself completely healthy—everyone has some kind of illness. Therefore, everyone can receive Unction once a year; and an announcement should be made in the church ahead of time so that everyone who wants to could come at the appointed time. Archpriests Anatoly and Vladimir agreed with Fr. John; nevertheless the Unction services at first took place not in the church, but at the home of my grandmother, Lydia Dimitrievna. This happened in February of 1967.

Two families gathered: that of Fr. Anatoly and of Fr. Vladimir. There were children and the elderly. The sacrament was served by Fr. John, my father and my uncle. They anointed everyone in order, and the priests anointed each other. After some time, the sacrament was served in the St. Nicholas Church, and then it was served yearly. I do not know how it was in other places, but this tradition gradually became widespread.

As for the allowed frequency of receiving Holy Communion, Fr. John said that everyone may receive once a month. He only blessed certain people to receive once every two weeks. I never heard of him blessing anyone to receive more often than that.

About confession, Fr. John said that in our time, both detailed and brief confessions are allowable. During the fasts, when there are great multitudes of people wishing to confess and receive the Holy Mysteries of Christ, there simply is no time for a detailed confession. When there is time, one should confess in detail; and when the time is short, there is nothing wrong with having a brief confession.

Fr. John left Kasimov on the second day of the feast of the Meeting of the Lord, on February 16, 1967, but we did not lose contact with him. Fr. John entered the Pskov-Caves Monastery [in Pechory, Pskov Province] as a monk—he had received the tonsure just before from Schema-Archimandrite Seraphim (Romanstov; canonized in 2010). I saw Fr. John in a klobuk and mantia for the first time when I came to visit him in the monastery. We children of Fr. Anatoly Pravdoliubov began visiting Pechory very often in order to receive Fr. John's blessing, hear his spiritual instructions, and pray at the monastery services.

The town of Pechory is located at such northern latitude that during the late spring and early summer, there are true "white nights," and during the winter, it is constantly dark. It would get light out by about 10:00 a.m., and by 4:00 p.m. it would be dusk. Thus, we would be going to church in the dark mornings, and by the evening services, it would almost be the dark of night. The number of pilgrims to the monastery greatly increased after Fr. John entered it. When we came to the monastery during the summertime, we would always meet some acquaintance there, either from Ryazan Province or from Moscow. There were significantly fewer pilgrims during the winter, and so we especially liked to go to Pechory during wintertime.

The train from Moscow arrived at the Pskov-Pechory station very early—at about five o'clock in the morning. The first bus that took people to the town would already be standing by the train station, and would depart while the train was still standing at the station. After Moscow life, people would find themselves in another world: quiet, white snow, frost, sidewalks sprinkled with sand and not salt as they were in Moscow. They would walk up to the monastery, the great gates of which would be yet closed. All would be silent, no one wanted to talk; they would wait until the monk-gatekeeper would open the gates. High above the gates hung a large icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, and a red icon lamp always burned before it. Finally, the monastery gates would slowly open and the pilgrims would enter the monastery grounds, one-by-one. Upon entering, they would make the sign of the cross, bow, and pass under the stone archway of the St. Nicholas church "over the gates," from whence began the "Bloody Path"[1] to the ancient church of the Dormition of the Mother of God, built into the caves. There, the brothers' moleben was about to begin. In the darkness of early morning, the figures of the monks could be seen hastening to the start of the moleben.

At that time in the Dormition Church, it was always dark. Only the icon lamps burned; even the candles on the candle stands would not yet be lit. That was the accepted order in the monastery, so that the brothers' moleben and midnight office would be served in the natural light of the lamps. The most important part of the moleben was the reading of the Gospel, Mt. 11:27–30: All things have been delivered to Me by My Father… Especially penetrating and meaningful sounded the words: Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. 30 For My yoke is easy and My burden is light. At the midnight office, of course, the most meaningful chant was the song, "Behold, the Bridegroom cometh at midnight…" The monks would be standing in the total darkness, in stately rows, before the icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God, the main holy shrine of the monastery, and sing simply, without haste, "The Bridegroom cometh at midnight, and blessed is that servant whom He shall find watching. But unworthy is he whom He shall find in slothfulness…" It seemed that the monks were contemplating these words rather than singing them. Fr. John never missed the brothers' moleben, and his voice could always be distinguished in this simple choir of monastery brethren.

After the moleben, Fr. John would go into the altar and stand before the table of oblation. He would remove particles of the prosphora to commemorate a multitude of people—those he knew and those who asked for his prayers. He would do this only up to the Cherubic Hymn, before which he would leave the table of oblation and no longer remove the particles. One day, he shared with us the feelings that he experienced during his prayers for people—the living and the reposed. He said, "It is as if people are walking past me; the closer it gets to the Cherubic Hymn, the faster they want to go past. They hurry each other along, as if pushing each others' shoulders, so that I can commemorate them in time…"

Our trips to Pechory became a necessity for us, and our parents only welcomed their children's initiative to go to the monastery, and to receive Fr. John's blessing for every important life step.

Fr. John blessed me for army service with an icon of St. Sergius of Radonezh. I also received his blessing before entering the seminary. When Fr. John blessed me, he said, "Enter the seminary, and then the Theological Academy." When I was already working on my dissertation, Fr. John blessed me with an icon of the Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian. The theme of my dissertation was very complicated—theological, Christological; and by blessing me with the icon of St. John the Theologian, Fr. John gave me to know that I would be able to tackle it.

When the time came for me to marry, my future wife, Liubov Dimitrievna, and I first went to see Fr. John, because we resolved to bind our lives together only if it be blessed.

Fr. John (Krestiankin).

We came to Fr. John and told him about our intention. Fr. John told us, "Today, after the evening service in the Dormition Church, there will be a monastic tonsure. Come and pray, and then we will decide whether you should take the tonsure, or enter into marriage."

You can imagine what feelings we took away from our meeting with Fr. John. For a whole twenty-four hours, we did not know what the answer would be, and in the evening we prayed in the Dormition Church, as Fr. John had told us to do. The monastic tonsure was performed in almost total darkness. Candles and icon lamps flickered, and the monks quietly sang, "In the Fatherly embrace..." The monk receiving the tonsure crawled along the stone floor in a long white gown, while the hieormonks and archimandrites, including Fr. John, covered him with their mantias. It was both solemn and sad. After the tonsure, we went back to the house where we were staying, and only the next evening were we with Fr. John again.

Without asking us anything, he blessed us for marriage with the icons of the Savior Made-Without-Hands and the "Jerusalem" Mother of God. We received invaluable instructions from him then. Fr. John talked about marriage as a sacrament, and said words that we have remembered all our lives. "A family is a domestic church," said Fr. John. "You should always have before your mental gaze the following picture: the icon of the Savior, the marriage bed, and the infant's cradle. Marriage is a sacrament. And what a miracle is the birth of children! "O Lord, Thou hast seen how my flesh was woven!" he cited from one of the psalms in the Russian translation.

Fr. John said that love never disappears in a Christian marriage; to the contrary, it grows more and more with every year, and the longer the spouses live together, the more they love each other.

I received Fr. John's blessing to become a deacon. At that time, I was subdeacon to His Holiness Patriarch Pimen. Having blessed me, Fr. John said, "Be in obedience to His Holiness the Patriarch: as he says, so let it be." I waited a rather long time… Finally, one day, after the Vigil in the Elokhov Cathedral,[2] when the curtain [on the royal doors] had already been drawn shut, I heard His Holiness Patriarch Pimen call me to his patriarchal place on the right side of the holy table, and then he said, "I am going to ordain you tomorrow." So, on Sunday, the fifth week of Great Lent, on the day of St. Mary of Egypt—April 1, 1979—His Holiness Patriarch Pimen ordained me a deacan and appointed me to serve in the church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul in Lefortovo.[3]

When I told Fr. John about this, he remembered the years of his imprisonment. "In 1950, I was imprisoned in Lefortovo prison," he said. Everyone who was with me in the prison cell could hear the ringing of the bells at the Sts. Peter and Paul Church. It is located near the prison; we would always know when important moments in the services were occurring, and we would pray especially fervently at that time."

After I had been ordained, I would come to the Pskov-Caves Monastery and serve with the monks… Sometimes I would be able to serve with Fr. John. This was a great consolation. One day, I served with Fr. John at the parish in the village of Yushkovo.

It was on the feast of St. Elias—the patronal feast of the parish. The church with the houses near it more resembled a monastery skete than a parish church. Fr. Paisy served there. He was a monk. Several elderly nuns lived at the church. Fr. Paisy always invited Fr. John to serve with him on that day, and Fr. John accepted his invitation for many years. Yushkovo is located about fifteen to twenty kilometers from Pechory, and therefore, having arrived that morning from Moscow, I was able to get to the church before the service started. When Fr. John saw me in the altar, he was very amazed, and asked, "How did you get here?" "I came especially to pray with you," I answered. "Will you serve?" asked Fr. John. "If you bless, I will," I said. "Definitely, serve!" said Fr. John.

That was a wonderful day! Before the beginning of the Liturgy, Fr. John served a moleben with an akathist to the Prophet Elias and a blessing of the waters. There were people near him, and everyone sang. After the Liturgy was a cross procession with a sprinkling of the people and the church. It was as if Fr. John was again serving in a parish. He talked with people, whole groups and families coming up to him. This was all at the parish, amidst the grasses and trees. The sun was shining, and it was very warm outside—the very height of summer! After the service and procession ended, Fr. John went to sprinkle the parish buildings with holy water. "Let's go, we'll sprinkle Maria's hut with holy water," he said, referring to the tiny house more resembling a hut that a house. Everyone had joyful smiles on their faces, and Nun Maria was simply elated that Fr. John had come to her house to sprinkle it with holy water.

Then there was a meal in Fr. Paisy's house. Again Fr. John talked with people, and there were very interesting conversations. One of the priests asked Fr. John if the Chernobyl catastrophe was apocalyptic, and could Chernobyl have been that very "Wormwood" cited in the book of Revelations? "I would not call that accident at the nuclear power plant a direct fulfillment of the Apocalypse," replied Fr. John. "One must relate very cautiously to any explanation of the book of Revelations, and there is a reason why the Church does not accept very many of the explanations regarding it. There is an explanation of the book of Revelations by St. Andrew of Cesarea—it is accepted by the Church, and it may be read. All the rest are very doubtful!" Fr. John also talked about how very bad it is when Church books and icons are sold in ordinary stores, next to very different products. "This should not be!" he said. He also said that every person should have a close connection with his guardian angel. In a word, the subjects of conversation were quite varied. Unfortunately, however, they did not last very long—Fr. John had to go back to the monastery.

A car was waiting for Fr. John at the foot of the hill on which the church stood—a "Volga," which Fr. Paisy had reserved earlier. We all descended the hill to that car, and Fr. John went up to the young driver and gave him a piece of candy. "No, thank you," the driver answered. Fr. John exclaimed, "What self-restraint!" There happened to be another car next to the "Volga"—a "Niva." The priest who had arrived in it drew Fr. John over to the car, asking him to go with him instead. "Where is your travelling companion, the tall, young man?" Fr. John inquired, because everyone had seen that priest in the church during the service, surrounded by a whole group of his parishioners. "There he is!" said batiushka, and opened the trunk of the Niva. In the trunk was a man, about thirty years old and two meters tall, literally doubled over. The priest had stuffed him in there in order to make room for Fr. John. "Have you no conscience?! What are you doing?! How could you treat a man like that?!" Fr. John said sternly. "I will not go with you!" He then instructed me to be seated in the back of the Volga, sat down next to me, and we drove back to the monastery, continuing our discussion.

The next day, that priest saw me in the monastery and said, "how I envy you: you drove together with Fr. John!"

Around the mid 1980's, the first confusion over the [social security] numbers started. At that time, it was not SSNs, but the new pension documents. People had to fill out some forms that required them to write a specific number, each form having its own. People started talking about the seal of Antichrist, and the unacceptability of such forms. People were always asking me how to relate to them. I considered that there wasn't anything particularly wrong with them, but I decided to ask the opinion of Fr. John. On one of my trips to Pechory, I told Fr. John in detail all about the people's concerns. Fr. John answered me personally in the following way. We must not fear any numbers. Numbers are everywhere: there are digits on watches, on documents, on the pages of books. We should instead fear the sins that we commit, and especially the temptations of these times. If we easily give in to these temptations, if we easily sin, then the spirit of antichrist is working in us, and the seal of antichrist could already be upon us, unnoticeably even to ourselves!

When the confusion over the SSNs arose, I asked him about this as well. Fr. John answered that everything he had said regarding the pension documents is applicable also to SSNs: we don't need to be afraid of any numbers!

I served in the church of Sts. Peter and Paul for a long time—eleven whole years. I became an Archdeacon, and served with a double orarion, but my desire was to serve in the priestly rank. I asked Fr. John several times for his blessing to submit a request to the Patriarch for ordination, but he answered, "The time has not yet come, it is still early." When they started calling me to Ryazan diocese, I went to get a blessing to transfer to that diocese. But Fr. John answered, "Under no circumstances! Stay where you are! You will be a priest. When the time comes, it will all happen by itself, without any requests! But for now, you shouldn't go looking for anything—that would be an asked-for cross, not your own, not from God, but from yourself. Over the course of twelve years, I was at six different parishes: Letovo, Nekrasova, Borets, Kasimov… but I never looked for anything. I was always transferred with various formulations: for the betterment of Church life, with regard to Church need… Never of my own asking! You, too—never go looking for anything; everything will come in its own time. By the way," added Fr. John, seeing my desire to transfer to another diocese, "You can do as you know best." "No, Fr. John, what are you saying?" I replied. "I will not take up anything without your blessing." It was obvious that Fr. John approved of this inclination [to follow his advice].