The Life of Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky), Archbishop of Verey

One of the most eminent figures of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1920s was Archbishop Hilarion of Verey, an outstanding theologian and extremely talented individual. Throughout his life he burned with great love for the Church of Christ, right up to his martyric death for her sake.

His literary works are distinguished by their strictly ecclesiastical content and his tireless struggle against scholasticism, specifically Latinism, which had been influencing the Russian Church from the time of Metropolitan Peter Moghila [of Kiev].

His ideal was ecclesiastical purity for theological schools and theological studies.

His continual reminder was: There is no salvation outside the Church, and there are no Sacraments outside the Church.

Archbishop Hilarion (Vladimir Alexeyevich Troitsky in the world) was born on September 13, 1886, to a priest’s family in the village of Lipitsa, in the Kashira district of Tula Province.

A longing to learn was awakened in him at an early age. When he was only five years old, he took his three-year-old brother by the hand and left his native village for Moscow to go to school. When his little brother began to cry from fatigue, Vladimir said to him, “Well, then, remain uneducated.” Their parents realized in time that their children had disappeared, and quickly brought them home. Vladimir was soon sent to theology school, and then to seminary. After completing the full seminary course, he entered the Moscow Theological Academy, and graduated with honors in 1910 with a Candidate degree in Theology. He remained at the Academy with a professorial scholarship.

It is worth noting that Vladimir was an excellent student from the beginning of theology school to the completion of the Theological Academy. He always earned the highest marks in all subjects.

In 1913 Vladimir received his master’s degree in theology for his fundamental work, “An Overview of the History of the Dogma of the Church.”

His heart burned with the desire to serve God as a monastic. On March 28, 1913, in the Skete of the Paraclete of the Holy Trinity–St. Sergius Lavra, he received the monastic tonsure with the name Hilarion (in honor of St. Hilarion the New, Abbot and Confessor of Pelecete, commemorated March 28). About two months later, on June 2, he was ordained a hieromonk, and on July 5 of the same year, raised to the rank of Archimandrite.

On May 30, 1913, Fr. Hilarion was appointed Inspector of the Moscow Theological Academy. In December of 1913 Archimandrite Hilarion was confirmed as Professor of Holy Scripture, in the New Testament.

Archimandrite Hilarion gained great authority both as an educator of those studying in the theological school and as a professor of theology, and his sermons earned him great renown.

His dogmatic theological works came out one after another, enriching ecclesiastical scholarship. His sermons sounded from church ambos like the ringing of bells, calling God’s people to faith and moral renewal.

When the question arose as to whether the Russian Church should restore the Patriarchate, as a member of the All-Russian Local Council of 1917–1918[1] he made an inspired stand in favor of the Patriarchate. He said:

The Russian Church has never been without a chief hierarch. Our Patriarchate was destroyed by Peter I. With whom did it interfere? With the conciliarity of the Church? But wasn’t it during the time of the Patriarchs that there were especially many councils? No, the Patriarchate interfered neither with conciliarity nor with the Church. Then with whom? Here before me are two great friends, two adornments of the seventeenth century—Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. In order to sow disagreement between these two friends, evil boyars whispered to the Tsar, “Because of the Patriarch, you, the Sovereign, have become invisible.” When Nikon left the Moscow throne, he wrote, “Let the sovereign have more space without me.” Peter gave flesh to this thought of Nikon’s when he destroyed the Patriarchate. “Let me, the Sovereign, have more space without the Patriarch …”

But Church consciousness, in the thirty-fourth Apostolic Canon, as well as in the Local Council held in Moscow in 1917, says one irrevocable thing: ‘The bishops of any nation, including the Russian nation, must know who is the first among them, and acknowledge him as their head.’

And I would like to address all those who for some reason still consider it necessary to protest against the Patriarchate. Fathers and brothers! Do not disrupt the joy of our oneness of mind! Why do you take this thankless task upon yourselves? Why do you make hopeless speeches? You are fighting againstthe Church’s consciousness. Have some fear, lest haply you begin to fight against God (cf. Acts 5:39)! We have already sinned— sinned in that we didn’t restore the Patriarchate two months ago, when we all came to Moscow and met with each other for the first time in the great Dormition Cathedral. Was it not it painful to the point of tears to see the empty Patriarchal seat?... And when we venerated the holy relics of the wonderworkers of Moscow and chief hierarchs of Russia, did we not hear their reproach, that for two hundred years their chief hierarchical throne has remained desolate?”

Immediately after the Bolsheviks came to power, they began to persecute the Church, and by March of 1919 Archimandrite Hilarion had already been arrested. His first imprisonment lasted three months.

On May 11/24, 1920, Archimandrite Hilarion was elected, and on the next day, consecrated as Bishop of Verey, a vicariate of the Moscow diocese.

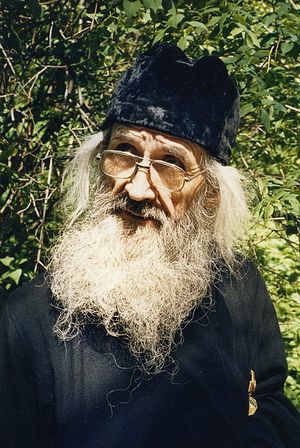

His contemporaries painted a colorful picture of him: young, full of cheerfulness, well-educated, an excellent preacher, orator, singer, and a brilliant polemicist—always natural, sincere, and open. He was physically very strong, tall, and broad-shouldered, with thick reddish hair and a clear, bright face. He was the people’s favorite.… Bishop Hilarion enjoyed great authority among the clergy and his fellow bishops, who called him “Hilarion the Great” for his mind and steadfastness in the Faith.

His episcopal service was a path of the cross. Two years had not passed since the day of his consecration before he was already in exile in Archangelsk. Bishop Hilarion was away from Church life for a whole year. He continued his activity upon his return from exile. His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon took a close interest in him, and made him, along with Archbishop Seraphim (Alexandrov),[2] his closest like-minded advisor.

The Patriarch raised Bishop Hilarion to the rank of Archbishopimmediately upon his return from exile. His ecclesiastical activities began to broaden. He carried on serious talks with Tuchkov[3] on the need to order life in the Russian Orthodox Church on the basis of canonical law, amidst the conditions present under the Soviet government; and he labored to restore ecclesiastical organization, composing a number of Patriarchal epistles.

He became a threat to the renovationists,[4] and was inseparable from Patriarch Tikhon in their eyes. On the evening of June 22/July 5, 1923, Vladyka Hilarion served an All-night Vigil for the feast of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God at the Sretensky Monastery, which had been taken over by the renovationists. Vladyka threw out the renovationists and re-consecrated the cathedral with the full rite of consecration, and thus returned the monastery to the Church. The next day, Patriarch Tikhon served in the monastery. The Divine Services lasted all day, not ending until 6:00 pm. Patriarch Tikhon appointed Archbishop Hilarion as Superior of Sretensky Monastery. The renovationist leader, Metropolitan Antonin (Granovsky), wrote against the Patriarch and Archbishop Hilarion with inexpressible hatred, accusing them unceremoniously as counter-revolutionaries. “Tikhonand Hilarion,” he wrote, “have produced ‘grace-filled,’ suffocating gases against the revolution, and the revolution has armed itself not only against the Tikhonites, but against the whole Church, as against a band of conspirators. Hilarion goes around sprinkling churches after the renovationists. He walks brazenly into these churches…. Tikhon and Hilarion are guilty before the revolution, vexers of the Church of God, and can offer no good deeds to excuse themselves.”[5]

Archbishop Hilarion clearly understood the renovationists’ lawlessness, and he conducted heated debates in Moscow with Alexander Vvedensky.[6] As Archbishop Hilarion himself expressed it, he had Vvedensky “up against the wall” at these debates, and exposed all his cunning and lies.

The renovationist bosses sensed that Archbishop Hilarion interfered with their doings, and they therefore exerted all efforts to deprive him of his freedom. In December 1923 Archbishop Hilarion was sentenced to three years in prison. He was taken to the prison camp in Kem,[7] and then to Solovki.[8]

When the archbishop saw the horrific conditions in the barracks and the camp food, he said, “We won’t get out of here alive.” Archbishop Hilarion had embarked upon the path of the cross, which culminated in his blessed repose.

Archbishop Hilarion’s path of the cross is of great interest to us, for in it is revealed the full magnificence of spirit of this martyr for Christ; therefore we will allow ourselves to take a more detailed look at this period in his life.

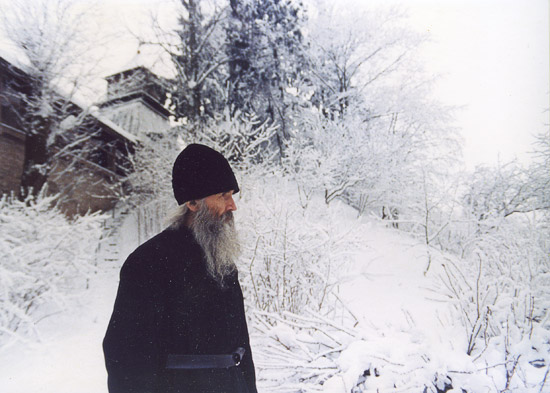

Living in Solovki, Archbishop Hilarion preserved all those good qualities of soul that he had gained through his ascetic labors, both before and during his monastic life and as a priest and hierarch. Those who lived with him during those years were witnesses to his total monastic non-acquisitiveness, deep simplicity, true humility, and childlike meekness. He simply gave away everything he had when asked.

He took no interest in his own things. That is why he needed someone to watch after his suitcase, out of mercy for him. He did have such an assistant at Solovki. Archbishop Hilarion could be insulted but he would never answer back; he might not even notice the attempt to insult him. He was always cheerful, and even if he was worried or distressed, he always tried to cover it up quickly with his cheerfulness. He looked at everything with spiritual eyes, and everything served for his spiritual profit.

“At the Philemonov fishery,” one eyewitness related, “four and a half miles from the Solovki kremlin and main camp, on the shores of the small White Sea bay, Archbishop Hilarion and I, along with two other bishops and a few priests (all prisoners), were net-makers and fishermen. Archbishop Hilarion loved to talk about this work of ours using a rearrangement of the words of the sticheron for Pentecost: ‘All things aregiven by the Holy Spirit: before, fishermen became theologians, and now it’s the opposite—theologians have become fishermen.’” Thus did he humble himself before his new lot.

His good spirits extended also to the Soviet authorities themselves, and he was able to view even them with guileless eyes.

Once, a young hieromonk was brought to Solovki from Kazan. He had been sentenced to three years of exile for removing the orarion[9] from a renovationist deacon, and not allowing the deacon to celebrate with him. The Archbishop approved of the hieromonk’s action, and joked about the various prison terms given to one or another person, having nothing to do with the seriousness of their “crime.” “For the Master is gracious and receives the last, even as the first,” he said in the words of St. John Chrysostom’s Paschal homily. “He gives rest to him that comes at the eleventh hour, just as to him who has labored from the first. He has mercy upon the last and cares for the first; to the one he gives, and to the other he is gracious. He both honors the work and praises the intention.” These words may have sounded ironic, but they imparted a feeling of peace, and made the hieromonk accept the trial as from God’s hands.

Vladyka Hilarion was greatly cheered by the thought that Solovki was a school of the virtues—non-acquisitiveness, meekness, humility, temperance, patience, and love of labor. One day a group of clergy was robbed upon arrival, and the fathers were very upset. One of the prisoners said to them in jest that this is how they were being taught non-acquisitiveness. Vladyka was elated by that remark. One exile lost his boots twice in a row, and walked around the camp in torn galoshes. Archbishop Hilarion was brought to unfeigned merriness looking at him, and that is how he encouraged good humor in the other prisoners. His love for every person, his attention to each one, and his sociability were simply amazing. He was the most popular individual in the camp, among all of its societal classes. We are saying not only that the general, the officer, the student, and the professor knew him and talked withhim (in spite of the fact that there were many bishops there, even older, and no less educated than he), but also the rabble, the criminal society of thieves and bandits, knew him as a good, respected person, whom it was impossible not to love. Whether during work-breaks or during his free time, he could be seen walking around arm in arm with one or another “example” of this crowd. This was not just condescension toward a “younger brother” or a fallen man—no. Vladyka spoke with each one as an equal, taking an interest in, for example, the “profession,” or favorite activity of each of them. The criminal element is very proud and sensitively conceited. They cannot be slighted with impunity. Therefore, Vladyka’s manner overcame everything. Like a friend to them, he ennobled them by his presence and attention. It was exceptionally interesting to observe him in that crowd, talking things over with them.

He was accessible to all; he was just like everyone, and it was easy to be around him, to meet with him and talk. The most ordinary, simple, and “non-saintly” exterior—that was Vladyka. However, behind this ordinary exterior of joy and seeming worldliness, one could gradually begin to see childlike purity, vast spiritual experience, kindness and mercy, his sweet indifference to material goods, his true faith, authentic piety, and lofty moral perfection—not to mention intellectual strength combined with strength and clarity of conviction. This appearance of ordinary sinfulness, foolishness-for-Christ, and a mask of worldliness hid his inner activity from people, and preserved him from hypocrisy and conceit. He was the sworn enemy of hypocrisy and all manner of “pious appearance,” and was absolutely conscious and direct. In the “Troitsky crew” (that is what they called Archbishop Hilarion’s work group) the clergy received a good education on Solovki. Everyone understood that there was no point in just calling yourself a sinner, carrying on long, pious conversations, or showing how austerely you lived. It was especially useless to think more highly of yourself than was actually the case.

Vladyka would ask every arriving priest in detail about the events leading up to his imprisonment. One day, a certain abbot was brought to Solovki. The Archbishop asked him, “What did they arrest you for?”

“Oh, I served molebens at home after they closed the monastery,” the abbot replied. “Well, people would gather, and there were even some healings …”

“Ah, well—even healings … How much Solovki did they give you?”

“Three years.”

“Well,” said Vladyka, “that’s not much; for healings they should have given you more. The Soviet government made an oversight …”

It goes without saying that it was more than immodest to speak about healings coming through one’s own prayers.

In mid summer of 1925, Archbishop Hilarion was sent to the prison in Yaroslavl. There it was very different from Solovki. He had special privileges there. He was allowed to receive spiritual books. Taking advantage of these privileges, Archbishop Hilarion read a great deal of patristic literature and kept notes, which resulted in many thick notebooks of patristic instruction. He was able to send these notebooks to his friends for safekeeping after passing the prison censor. The hierarch would secretly visit the prison warden, who was a kind man, and as a result he made an underground collection of religious manuscripts and Soviet literature, as well as copies of various Church-administrative documents and correspondence with bishops.

During that time, Archbishop Hilarion also courageously bore a slew of troubles. When he was in Yaroslavl prison, the Gregorian schism[10] was occurring within the Russian Church’s bosom. An agent from the GPU came to him since he was a popular bishop, and tried to persuade him to join the new schism. “Moscow loves you—Moscow is waiting for you,” the agent said to him. But Archbishop Hilarion remained steadfast. He couldsee what the GPU was trying to do, and he courageously rejected the sweet freedom offered him in exchange for his betrayal. The agent was amazed at his courage and said, “It’s nice to speak with such an intelligent man.” Then he added, “How long is your term on Solovki? Three years?! For Hilarion—only three years?! So little?” It is not surprising that three more years were added to Archbishop Hilarion’s sentence after this. The statement “for spreading government secrets” was also added; that is—for talking about his conversation with the agent in the Yaroslavl prison.

In the spring of 1926, Archbishop Hilarion was sent back to Solovki. His way of the cross continued. The Gregorians did not leave him in peace. They did not lose hope that they might be able to win such an eminent hierarch as Archbishop Hilarion over to their side, and thus strengthen their position.

In early June of 1927, when the White Sea had only just become passable, Archbishop Hilarion was transferred to Moscow for discussions with Archbishop Gregory. In the presence of various secular personages, the latter insistently requested Archbishop Hilarion to “gather courage” and head the Gregorian “Supreme Church Council,” which was rapidly losing its significance. Archbishop Hilarion categorically refused, explaining that the actions of this council were unjust and a waste oftime, contrived by people who knew neither Church life nor canons, and therefore the Council was doomed to failure. Moreover, Archbishop Hilarion counseled Archbishop Gregory as a brother to abandon his plans, which were unnecessary and even harmful to the Church.

Such meetings were repeated several times. They begged Vladyka Hilarion, promised him total freedom of action and a white klobuk,[11] but he firmly held to his convictions. There are even rumors that he said to someone at one of these meetings, “Although I’m an archpastor, I’m a hot-tempered man, and I urge you to leave. After all, I might lose my self-control.”

“I would sooner rot in prison than change my position,” he said once to Bishop Gervasius.[12] He stuck to this position on the Gregorians to the end of his life.

During the troubled times when, after the renovationist schism, disagreements had penetrated into the midst of the exiled bishops on Solovki, Archbishop Hilarion was a true peacemaker among them. He was able to unify them on the basis of Orthodox principles. Archbishop Hilarion was one of the bishops who worked on the Church declaration of 1926, which determined the position of the Orthodox Church under the new historical conditions. This declaration played an enormous role in the struggle with emerging divisions.[13]

In November 1927, certain of the Solovki bishops began to waiver over the Josephite schism.[14] Archbishop Hilarion was able to gather up to fifteen bishops in the cell of Archimandrite Theophan, where all unanimously resolved to preserve faithfulness to the Orthodox Church headed by Metropolitan Sergius.

“No schisms!” Archbishop Hilarion proclaimed. “No matter what they say to us, we will look at it as a provocation!”

On June 28, 1928, Vladyka Hilarion wrote to his close friends that he was unsympathetic in the extreme with those who had broken off, and considered their actions unfounded, foolish, and extremely harmful. He considered such separation to be an “ecclesiastical crime,” quite serious under the current conditions. “I see absolutely nothing in the actions of Metropolitan Sergius and his Synod that would exceed a measure of condescension and patience,” he said.

Archbishop Hilarion worked very hard to convince Bishop Victor (Ostrovidov) of Glazov,[15] who was very closely aligned with the Josephites. He finally did manage to convince Bishop Victor, and not only did the latter recognize that he was wrong—he even wrote a letter to his flock enjoining them to cease their separations.

Although Archbishop Hilarion was unable to know everything about the life in the Church of that time, he nevertheless was not an indifferent observer of the various ecclesiastical disturbances and catastrophes that were crashing down upon the Orthodox people. People came to him for advice and asked him what they should do to attain peace in the Church under the new conditions of political life. This was a very complicated question, and Archbishop Hilarion provided an exceedingly deep and well analyzed answer, based upon Orthodox canons and ecclesiastical practice.

Here is what he wrote about this in a letter dated December 10, 1927:

I have not participated for the last two years in Church life; I have only periodic and, perhaps, inexact information. Therefore, it is difficult for me to judge about the particulars and details of that life; but I think that the general line of Church life and its inadequacies and illnesses are known to me. The main inadequacy, one which I felt even earlier, is the lack of Church Councils since 1917—that is, during the very time when they have been most needed, because the Russian Church has entered into entirely new historical conditions, not without God’s will. These conditions are unusual, and significantly different from its earlier conditions. Ecclesiastical practice, including the formation of the Councils of 1917–1918, is not suited to these new conditions. The situation has become significantly morecomplicated since the death of Patriarch Tikhon. The question of the Locum Tenens, as far as I know, is also very confused, and ecclesiastical governance is in a state of total disarray. I do not know if there is anyone among our hierarchy, or even among conscious members of the Church in general, who are so naïve or near-sighted as to entertain the absurd illusion that the Soviet government will soon be overthrown and [the old order] restored, etc. But I think that all who desire the good of the Church recognize the need for the Russian Church to make a place for itself under the new historical conditions.

Thus, a Council is needed; and first of all we need to ask the governmental authorities to allow us to call a Council. However, someone needs to gather the Council, make the necessary preparations—in a word, lead the Church up to a Council. Therefore, right now, before the Council, an ecclesiastical body is needed. I have a series of requirements for the organization and the activity of this body which, I think, are common to everyone who wants good ecclesiastical order rather than disturbance of peace or some new confusion. I will point out a few of these requirements.

1. A temporary ecclesiastical body should not be essentially self-willed; that is, it should have the agreement of the Locum Tenens from the start.

2. As much as possible, the temporary ecclesiastical body should include those who have been delegated by the Locum Tenens, Metropolitan Peter (Polyansky) or the Holy Patriarch.

3. The temporary ecclesiastical body should unite and not separate the episcopate. It is not a judge, and not a punisher of dissenters—that is what the Council will be.

4. The temporary ecclesiastical body should see its task as modest and practical: the creation of a Council.

The last two points require particular explanation. The repulsive ghost of the 1922 VTsU (Supreme ChurchAdministration)[16] still hovers over the hierarchy and ecclesiastical personages. Church people have become suspicious. The temporary ecclesiastical body should fear like fire the least resemblance in activity to the criminal activity of the VTsU. Otherwise, there will only be new confusion. The VTsU was begun with lies and deceit. Everything should be founded upon the truth. The VTsU, an entirely self-appointed body, proclaimed itself as the supreme master of the destiny of the Russian Church—a master to whom ecclesiastical laws, and even common Divine and human laws, do not necessarily apply. Our ecclesiastical body will only be temporary, with the sole task of calling a Council. The VTsU persecuted all who would not submit to it—that is, all decent hierarchs and other ecclesiastical workers. Threatening punishments left and right, and promising mercy to the submissive, the VTsU evoked the censure of the government—censure that the government itself hardly found desirable. This repugnant side of the criminal activities of the VTsU and its successor, the socalled “Synod,” with its councils of 1923–1925, earned them deserved contempt, caused great woe and suffering for innocent people, brought only evil, and had only the result that a part of the hierarchy and some irresponsible Church people left the Church and formed schismatic groups. Nothing of the kind, not even the slightest hint, should be present in the activities of the temporary ecclesiastical body. I emphasize this thought especially, because I see a very great danger in precisely this. Our ecclesiastical body should convoke a Council. With respect to this Council, the following requirements are necessary.

5. The temporary ecclesiastical organ should convoke, but not select the members of the Council, as was done by the VTsUof woeful memory in 1923. A selected Council will not have any authority and will bring not calm, but only new confusion to the Church. There is scant need to enlarge the list of “robber councils” in history—three are enough: Ephesus in 449, and two in Moscow, between 1923 and 1925. My first wish for the future Council is that it would prove its total non-participation and non-solidarity with all politically suspect movements, to disperse the fog of unconscionable and foul-smelling slander which has shrouded the Russian Church through the criminal efforts of evil doers (of renovation). Only a true Council can have authority, bring calm into Church life, and give peace to the tormented hearts of Church people. I believe that at the Council, the whole importance of this ecclesiastical moment will come to the surface, and it will order Church life in a way that corresponds to the new conditions.

As Archbishop Hilarion thought and confirmed, only if there was Church sobornost [conciliarity] could there be pacification, and could the Russian Orthodox Church conduct its normal activities within the new conditions of the Soviet state.

His way of the cross was coming to its completion. In December 1929 Archbishop Hilarion was sent to live in Alma-Ata in Central Asia for a term of three years. He traveled under guard from one prison to another. He was robbed along the way, and when he arrived in Leningrad he was in a long shirt, swarming with parasites, and was already sick. He wrote from the Leningrad prison where he had been placed, “I am seriously ill with louse-borne typhus, and am lying in a prison hospital. I was most likely infected on the road; on Saturday, December 28, my fate will be decided (the crisis of the illness). I am unlikely to survive.”

In the hospital he was told that he needed to be shaved, to which His Eminence replied, “Do what you want with me.” In his delirium he said, “Now I’m completely free; no one can take me.”

The angel of death already stood by the head of the sufferer. A fewminutes before he died, a doctor came up to him and said that the crisis was over and he might recover. Archbishop Hilarion said, in a barely audible whisper, “How good! Now we’re far from…” With these words, the confessor of Christ died. This was on December 15/28, 1929.

Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov), who occupied the Leningrad see at the time, obtained permission to take his body for burial. They brought white hierarchical vestments and a white miter to the hospital. They vested him and took him to the church of the Novodevichy Monastery in Leningrad. Vladyka had changed terribly. In the coffin lay a pitiful, shaven, gray old man. When one of his relatives saw him in the coffin, she fainted—he was so unlike the former Hilarion.

He was buried in the Novodevichy Monastery cemetery, not far from the graves of the relatives of then Archbishop, later Patriarch, Alexei (Simansky).[17]

Besides Metropolitan Seraphim and Archbishop Alexei, Bishop Ambrose (Libin) of Luga, Bishop Sergius (Zenkevich) of Lodeinoe Polye, and three other bishops participated in the burial.

Thus this spiritual and physical giant departed to eternity—a man of wondrous soul, gifted by the Lord with outstanding theological talents, who laid down his life for the Church. His death was an enormous loss for the Russian Orthodox Church.

May your memory be eternal, holy Hierarch Hilarion!

Translated by Nun Cornelia.

Editor’s Note

On April 27/May 10, 1999, Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion, Archbishop of Verey, was glorified as a saint by the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

On the eve of his canonization, the Holy Hieromartyr’s relics were translated from St. Petersburg to Moscow and placed in the church ofthe Sretensky Monastery. At the solemn service, which drew a multitude of pilgrims to the monastery, His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II read the resolution on his glorification, and lit a perpetual lamp over the shrine containing his holy relics.

St. Hilarion is commemorated twice a year: on December 15/28, the day of his martyric repose, and on April 27/May 10, the day of his glorification.

St. Hilarion left a large body of homilies and apologetical writings, many of which can be found in Russian on the web site of Sretensky Monastery,

http://www.pravoslavie.ru, and a few of which have been published in English. Here are the titles of some of them:

Christianity and Socialism[18]

Christianity or the Church?[19]

Holy Scripture and the Church[20]

Holy Scripture, the Church, and Science

The Incarnation and the Church

On Entertainment for Charity

From the Academy to Mount Athos: In the East and the West

The Incarnation and Humility

The Incarnation

Prophetic Schools of the Old Testament

Pascha of Incorruption

Letters about the West

Progress and Transfiguration

Sin against the Church: Thoughts on the Russian Intelligentsia

Why Is It Necessary to Restore the Patriarchate?

The Restoration of the Patriarchate and the Election of the Patriarch ofAll Russia

There Is No Christianity without the Church

Metropolitan John (Snychev) of St. Petersburg and Ladoga (†1995)

Orthodox Word

09 / 05 / 2011

[1] The All-Russian Local Council was the first Church Council in Russia since the abolition of the Patriarchate at the Council of 1681–1682. Its sessions lasted from August 1917 to September 1918.—Ed.

[2] Later Metropolitan of Kazan and Sviyazhsk, he was shot by the Bolsheviks in 1937.—Ed.

[3] Yevgeny Alexandrovich Tuchkov was the plenipotentiary for Church affairs of the GPU, the forerunner of the KGB. He was responsible for disrupting the Russian Church in every possible way, including the use of mass arrests and the execution of clergy, as well as open support for the “Living Church” (see note 4 below).—Ed.

[4] That is, members of the “Living Church,” an organization that attempted to supplant the Russian Orthodox Church while reforming Orthodox teachings, traditions and practices according to modern liberal ideas.

[5] Izvestia, September 23, 1923.—Ed.

[6] Alexander Vvedensky was a liberal priest who, from 1923 until his death in 1946, was one of the leaders of the “Living Church.”—Ed.

[7] Kem, a city in Karelia, had a prison camp that was used from 1926 to 1939 as a departure point for political prisoners who were being sent to Solovki.—Ed.

[8] The Monastery of Solovki, located on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, was turned into a labor camp after the Bolshevik revolution. In 1926 it became a prison camp, and remained so until its closure in 1939. It was reopened as a monastery in 1990.—Ed.

[9] Orarion: a narrow stole worn by Orthodox deacons over the left shoulder.

[10] The Gregorian schism, so-called after its founding bishop, Gregory (Yakovetsky), was a new schism fostered by the Soviet authorities after the obvious failure of the renovationists. It was essentially a council of bishops, submissive to and therefore legalized by the Soviet authorities. These bishops claimed to govern the Church after the death of Patriarch Tikhon, since the Locum Tenens, Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsa, was imprisoned. They differed from the renovationists in that they recognized both the reposed

Patriarch Tikhon and the Locum Tenens (since he was in prison, and therefore could not interfere), and were overtly traditionalist.—Trans.

[11] Klobuk: a type of monastic head covering. A white klobuk, instead of a black one, is given to a hierarch in the rank of metropolitan.—Trans.

[12] Bishop of Rostov and Uglich, he joined the “Living Church” in 1925 and eventually even renounced God.—Ed.

[13] The author is referring to Archbishop Hilarion’s initiative in the memorandum composed by a council of bishops on Solovki on the separation of Church and State, and the possibility of the Church’s existence under a regime that was ideologically diametrically opposed to the Orthodox Church and everything it believes in and stands for. It took the stance that the Church should not involve itself in politics, but by the same token, the State should not interfere with the regular life of the Church. “The memorandum concludes that if the Soviet government accepts these conditions of coexistence, then the Church ‘will rejoice in the justice of those on whom such policies depend. If … not, she is ready to go on suffering, and will respond calmly, remembering that her power is not in the wholeness of her external administration, but in the unity of faith and love of her children; but most of all she lays her hopes upon the unconquerable power of her divine Founder’” (Dimitry Pospielovsky, The Russian Church Underthe Soviet Regime 1917–1982 [Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1984],

vol. 1, pp. 142–46).—Trans.

[14] Named for Metropolitan Joseph (Petrovykh) of Petrograd, who separated from Metropolitan Sergius over the latter’s declaration of loyalty to the Soviet regime and was one of the leaders of the early underground Church in Russia. The present article was written in the 1960s, during a period of “standoff ” between the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia over the relative correctness of Metropolitan Sergius’ actions and those of the hierarchs who disagreed with and separated from him. Arguments of the supporters and detractors of the declaration of Metropolitan Sergius, such as those presented in this article, were purposely set aside in 2007, with the reunion of the two parts of the Russian Church.

In 1981 Metropolitan Joseph was canonized among the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, and he continues to be held in high esteem by Russian believers both within and outside their motherland. When the Moscow Patriarchate canonized the New Martyrs and Confessors in 2000, among the newly canonized saints were hierarchs and clergymen who had supported and commemorated Metropolitan Sergius, as well as those who had opposed his policies and had not commemorated him as chief hierarch. By this the Patriarchate “legitimatized” a plurality of views concerning the complex and extremely difficult period of the Russian Orthodox Church under the Soviet regime.—Ed.

[15] New Hiero-confessor Victor (†1934) was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in 1981, and by the Moscow Patriarchate in 2000. He is commemorated on April 19 and June 18.—Ed.

[16] In May 1922, members of the “Living Church” schism illegally took over administration of the Church, taking advantage of the fact that Patriarch Tikhon was then under house arrest.—Trans.

[17] Patriarch Alexei I of Moscow and All Russia.

[18] Published in English in Orthodox Life, May–June 1998, pp. 35–44.

[19] Published in English by Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, N.Y., 1985.

[20] Published in this issue of The Orthodox Word.

http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/33316.htm

.jpg/220px-%D0%A1%D0%B2%D1%8F%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%8C_%D0%A2%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%BE%D0%BD_(%D0%91%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%BD).jpg)